Continuous Delivery Pipeline

Our highest priority is to satisfy the customer through early and continuous delivery of valuable software.

— Agile Manifesto

Talk to Learning Advisor

Continuous Delivery Pipeline

Continuous Delivery Pipeline Courses

Coming Soon

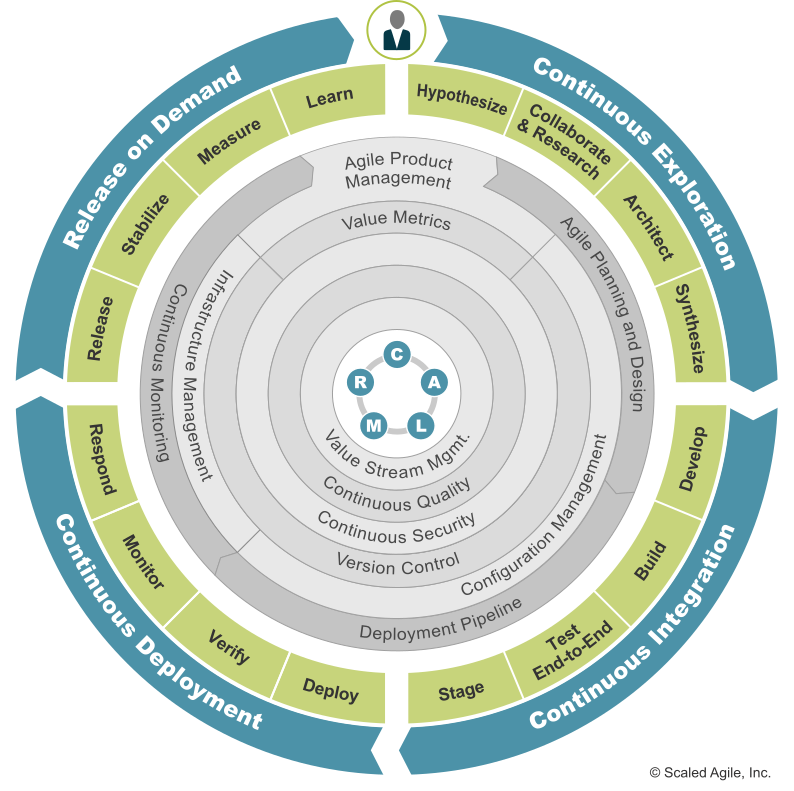

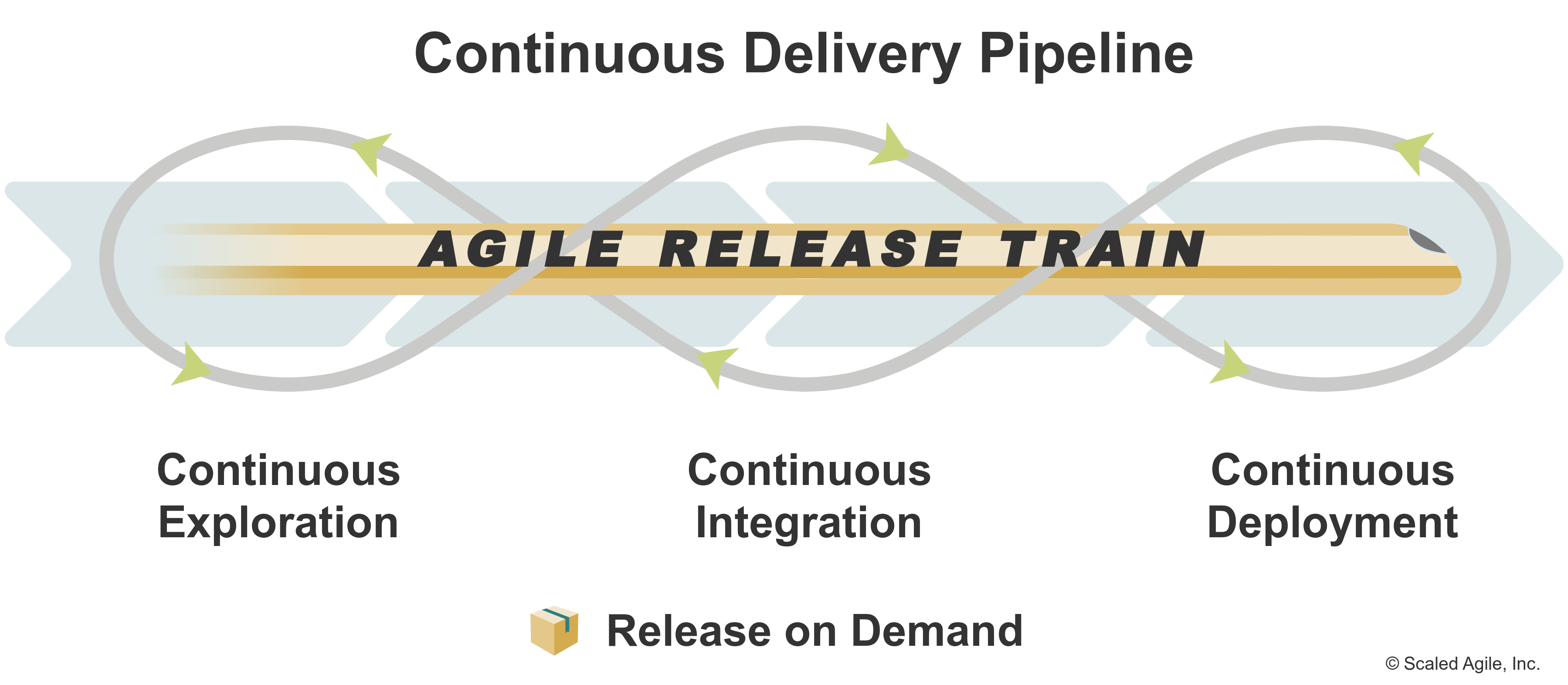

The Continuous Delivery Pipeline (CDP) is a significant element of the Agile Product Delivery competency. Each Agile Release Train (ART) builds and maintains, or shares, a pipeline with the assets and technologies needed to deliver solution value as independently as possible. The first three elements of the CDP (CE, CI, and CD) work together to support the delivery of small batches of new functionality, which are then released to fulfill market demand.

Details

Building and maintaining a CDP allows each ART to deliver new functionality to users far more frequently than traditional processes. For some, continuous may mean daily or even releasing multiple times per day. For others, it may mean weekly or monthly releases—whatever satisfies market demands and the goals of the enterprise.

Legacy practices often cause ARTs to make solution changes in large monolithic chunks. However, this does not usually need to be an all-or-nothing approach. For example, a satellite system comprises a manufactured orbital object, a terrestrial station, and a web farm that feeds the acquired data to end users. Some components may be released daily—perhaps the web farm functionality or satellite software. Other elements, like the hardware components, can only be done once every launch cycle.

Decoupling the web farm functionality from the physical launch eliminates the need for a monolithic release. It also increases Business Agility by allowing the delivery of solution components in response to frequent market changes.

The Four Aspects of the Continuous Delivery Pipeline

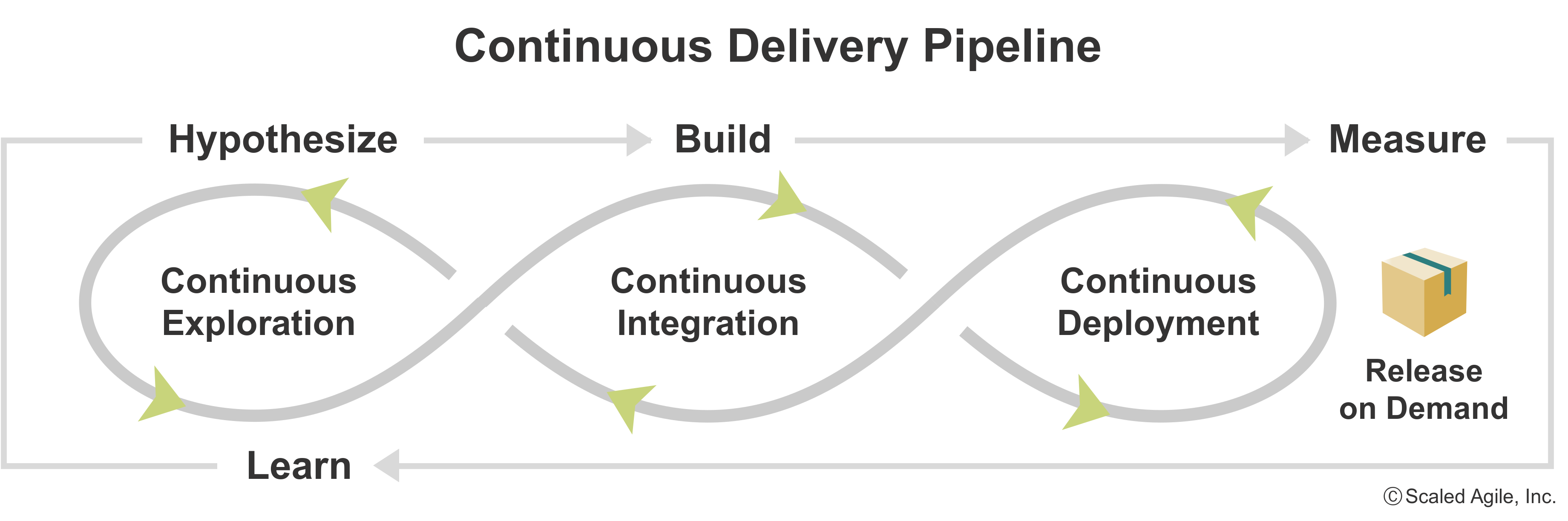

The SAFe CDP contains four aspects: continuous exploration, continuous integration, continuous deployment, and release on demand. The CDP enables organizations to map their current pipeline into a new structure and use relentless improvement to deliver value to customers. Internal feedback loops often identify process improvements, while external feedback identifies solution improvements. The improvements collectively create synergy in ensuring the enterprise is ‘building the right thing, the right way’ and frequently delivering value to the market. The paragraphs below describe each aspect.

- Continuous Exploration (CE) focuses on creating alignment on what needs to be built. In CE, design thinking ensures the enterprise understands the market problem or customer need and the solution required to meet that need. It starts with a hypothesis of something that will provide value to customers. Ideas are then analyzed and further researched, leading to the understanding and convergence of the requirements for a Minimum Viable Product (MVP) or Minimum Marketable Feature (MMF). These feed the solution space for exploring how existing architectures and solutions can or should, be modified. Finally, convergence occurs by understanding which Capabilities and Features, if implemented, are likely to meet customer and market needs. Collectively, these are defined and prioritized in the ART Backlog.

- Continuous Integration (CI) focuses on taking features from the ART backlog and implementing them. In CI, the application of design thinking tools in the problem space focuses on the refinement of features (for example, designing a user story map), which may motivate more research and the use of solution space tools (such as user feedback on a paper prototype). After specific features are clearly understood, Agile Teams implement them. Completed work is committed to version control, built and integrated, and tested end-to-end before being validated in a staging environment.

- Continuous Deployment (CD) takes the changes from the staging environment and deploys them to production. At that point, they’re verified and monitored to ensure they are working correctly. This step makes the features available in production, where the business determines the appropriate time to release them to customers. This aspect allows the organization to respond, rollback, or fix forward when necessary.

- Release on Demand (RoD) is the ability to make value available to customers together or in a staggered fashion-based on market and business needs. This approach allows the business to release when market timing is optimal and carefully controls the risk associated with each release. Release on demand also encompasses critical pipeline activities that preserve solutions’ stability and enduring value long after release.

Although described sequentially, the pipeline isn’t strictly linear. Instead, it’s a learning cycle that allows teams to establish one or more hypotheses, build a solution to test each one, and learn from that work, as Figure 2 illustrates.

Although a single feature flows through the Value Stream sequentially, the teams work through all aspects in parallel. That means that ARTs and Solution Trains, throughout every PI and every iteration in the PI, continuously:

- Explore user value

- Integrate and demo value

- Continuously deploy to production

- Release value whenever the business needs it

Start by Mapping the Current Workflow

Successful enterprises already have a delivery pipeline—otherwise, they wouldn’t be able to release any value. But too often, they are not fully automated, contain significant delays, and require tedious and error-prone manual intervention. These factors cause organizations to delay releases, increasing their size and scope (“We’ll release when it is big enough”). This approach is the opposite of the SAFe Principle #6, which makes value flow without interruption.

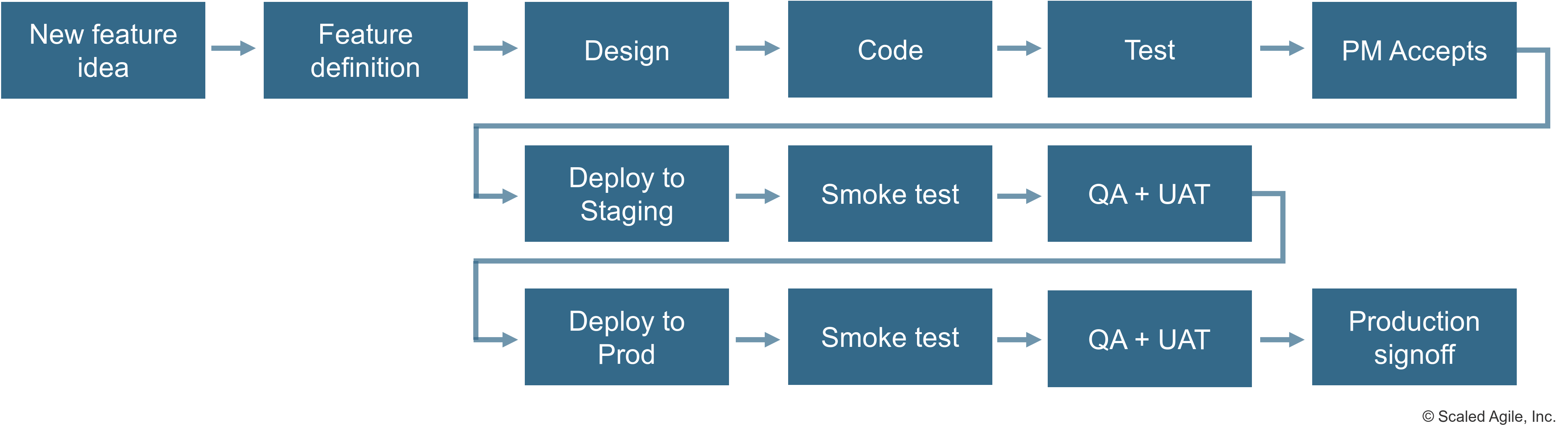

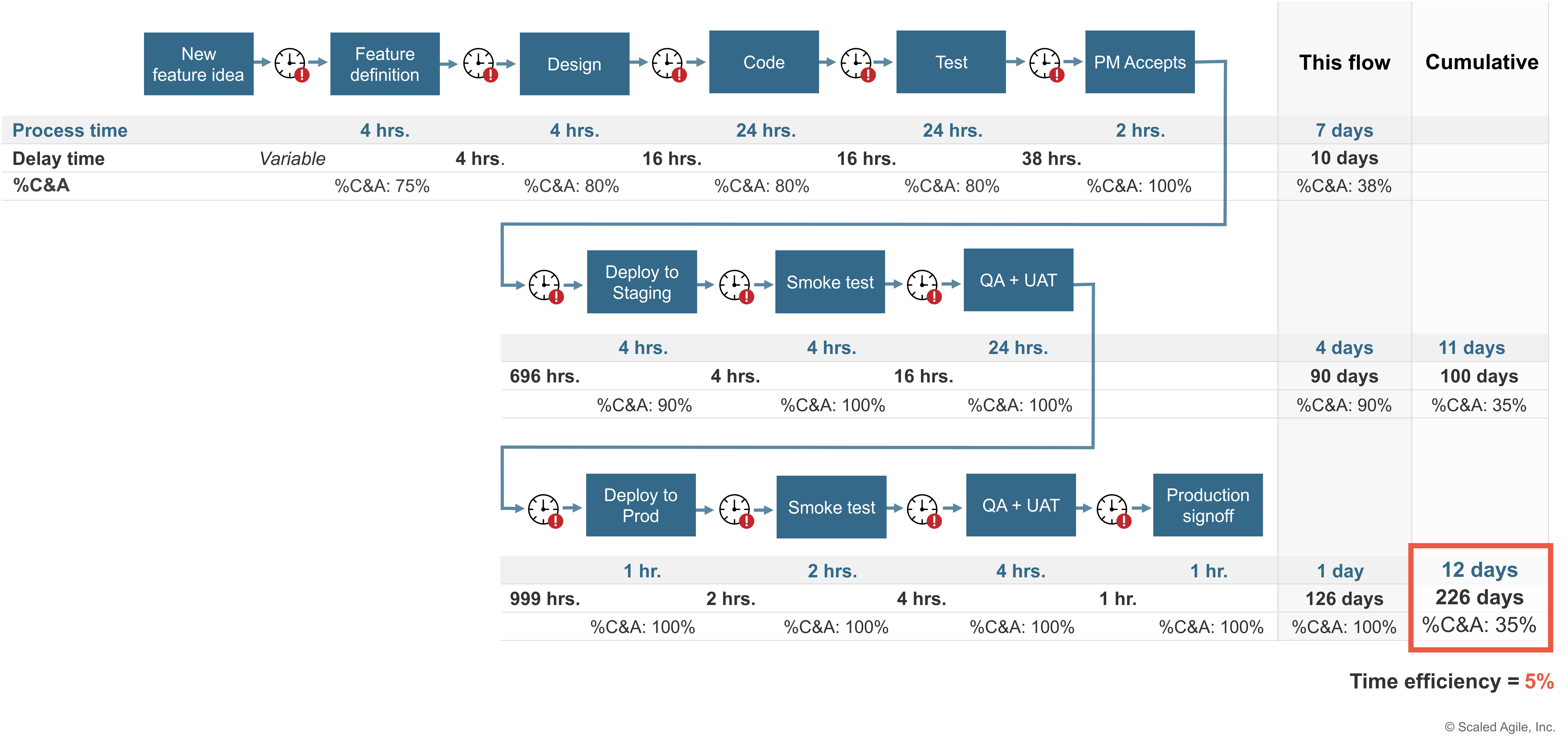

The first step to improving value flow is mapping the current pipeline. Figure 3 illustrates the flow of value through one enterprise’s CDP, focusing initially on new Feature development. Over time, this map would be extended to capture any change to the system, from new Features to maintenance to architectural improvements.

Once the current pipeline has been mapped, metrics can be collected and recorded on the value stream map to understand where delays occur. These metrics enable the ART to identify opportunities for improvement (such as eliminating delays or reducing rework). Four primary metrics [1] are used (Figure 4):

- Process time is the time it takes to get work done in one step. For example, in Figure 4, the ‘Design’ step takes four hours.

- Lead time is the time it takes from when the work was done in the previous step until it’s done in the current step. In other words, lead time = delay time from the last step + process time of the current step. In Figure 4, the lead time from creating ideas to defining them is variable. It is common when first mapping systems not to have metrics on specific steps. In this case, the ART can improve the remaining process while metrics are gathered on the variable part.

- Delay time is the time when no work is happening. Figure 4 shows that the features accepted by the Product Manager are delayed a staggering 696 hours before being deployed to staging. Understanding and eliminating unnecessary delays is critical to improving the flow of value.

- Percent complete and accurate (%C&A) represents the percentage of work that the next step can process without needing rework. Often, delays are caused by poor quality in the upstream (prior) steps. The %C&A metric helps identify the steps where poor quality might be occurring and causing longer lead times, resulting in delays in value delivery. Figure 4 indicates that 20% of the time, the work moving from the ‘Design’ step to the ‘Code’ step needs to be reworked. Improving the %C&A metric is also essential to improving the flow of value. The %C&A of a single step is extended to rolled %C&A, a measure that captures the likelihood that an item will pass through the entire workflow without rework. With a cumulative rolled %C&A of 35%, this workflow is reworking more than half of its steps.

Working ‘Software’ over Comprehensive Documentation

Tracking Continuous Delivery

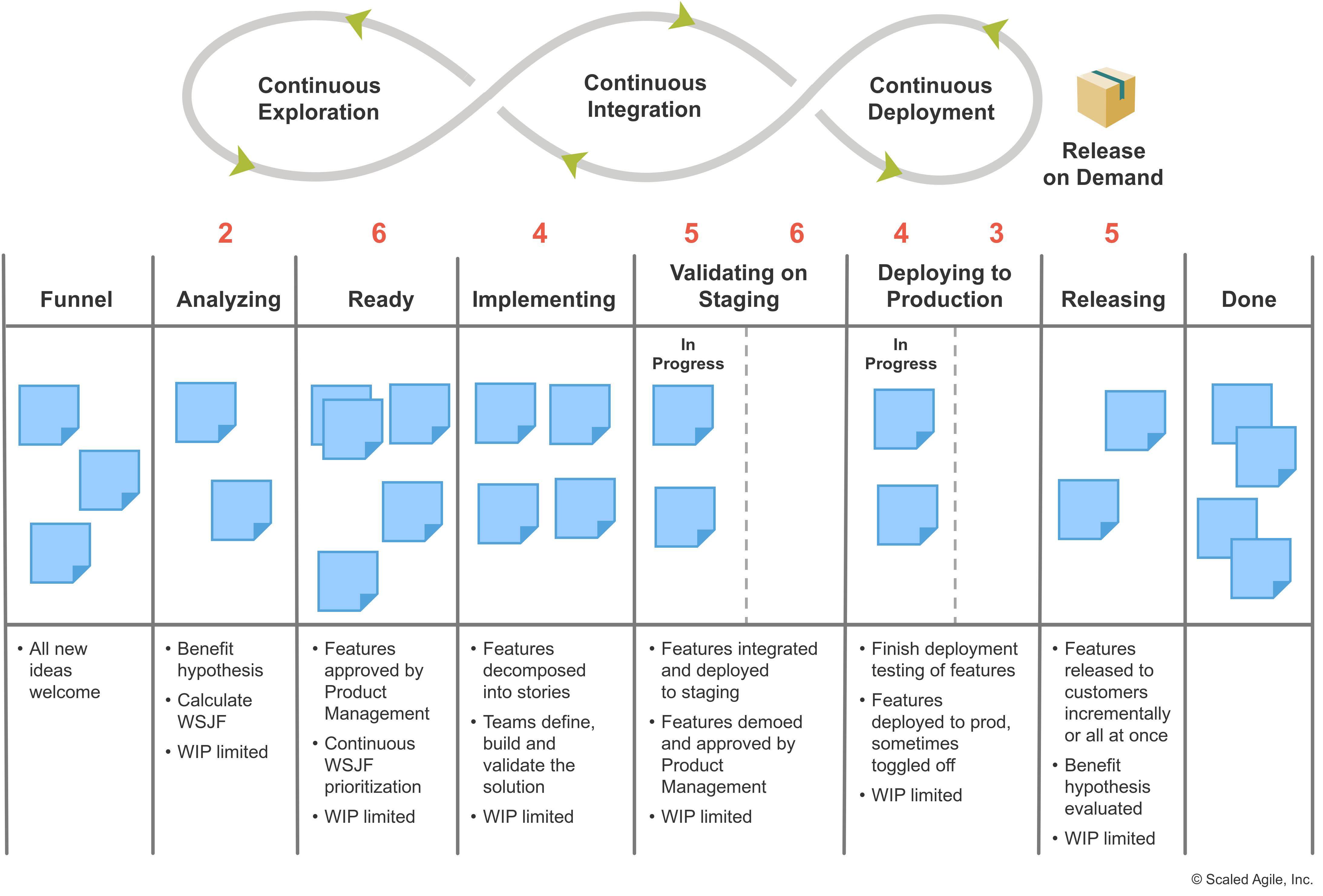

The Kanban systems consist of a series of states, each of which is summarized below:

- Funnel – This is the capture state for all new features or enhancement of existing system features.

- Analyzing – Features that best align with the vision are pulled into the analyzing step for further exploration. Here they’re refined with critical attributes, including the business benefit hypothesis and acceptance criteria.

- Ready – After analysis, higher-priority features move to the backlog, where they’re ranked.

- Implementing – At every PI boundary, top features from the ART backlog are pulled into the implementing stage, where they’re developed and integrated into the system baseline.

- Validating on staging – Features ready for feedback get pulled into this step to be integrated with the rest of the system in a staging environment and then tested and validated.

- Deploying to production – When capacity is available, features are deployed into the production environment, where they await release.

- Releasing – Features are released once a sufficient amount of value has been created to meet market demands and the benefit hypothesis is evaluated.

- Done – When the hypothesis has been satisfied, no further work on the feature is necessary, and it moves to the done column.

Enable the Continuous Delivery Pipeline with DevOps

Individuals and Interactions over Processes and Tools

Working ‘Software’ over Comprehensive Documentation

Customer Collaboration over Contract Negotiation

Responding to Change over Following a Plan

Change is a reality in the digital age and essential to achieving agility. The strength of Lean-Agile is in how it embraces change. As the system evolves, so does the understanding of the problem and the solution domain. Business stakeholder knowledge also improves over time, and customer needs evolve as well. Indeed, those changes add value to our system.

Of course, planning is an essential part of Agile. In fact, Agile teams and teams-of-teams plan more often and more continuously than their waterfall counterparts. However, plans must adapt as new learning occurs, new information becomes visible, and the situation changes. Worse, evaluating success by measuring conformance to a plan drives the wrong behaviors (for example, following a plan in the face of evidence that the plan is not working).